6

Action

Capable new tools for collaborative action are poised to shift sovereignty back to small communities at more appropriate fidelity of empowered placemaking. Together, these tools can help us build a persistent community memory capable of carrying our places forward with vitality.

For an enduring community memory to sustain us, we must act to perpetuate it. The most important of such acts are simple: to listen to a friend or plant a tree. Still, there are some ways that community computing can help us grow in deeper relationship to our neighbors and our place. So finally, let’s get into some specific near-term use cases for these technologies.

The following discussion should be viewed as a limited view, drawing from the many brilliant and dedicated people building these tools. In reality, the open nature of these systems means that specific uses cannot be prescribed or predicted very far in advance.

Digital Identity

And other foundations for digital governance

Establishing a reliable digital identity system has been lauded as something of a technological holy grail, unlocking new connections between the digital and physical. Concerningly, most commonly imagined identity architectures pass through large institutions or corporations. A state-organized digital identity system, integrated with a state-managed payment platform, powered by a sovereign state currency would be the perfect kind of surveillance state panopticon.

As an alternative, several kinds of ‘self-sovereign (digital) identity’ (SSI) systems have been proposed to give individuals autonomy and authority over how their identity and accompanying data is used and verified. There are plenty of difficult compromises to work through before we get to self-sovereignty, though—such as, if the data management is truly self-sovereign, then who is establishing and verifying its truth?

Even while considering the many worthwhile efforts at universal digital identity systems, it is important to remember that identity has historically been constructed through relationship at the local level. And so, there is plenty of room today for iterative and informal experiments in community-sovereign identity in our home places—experiments that may help to mature innovations in community computing, which have until now been used mostly for the speculative games of technologists.

Reputation Systems

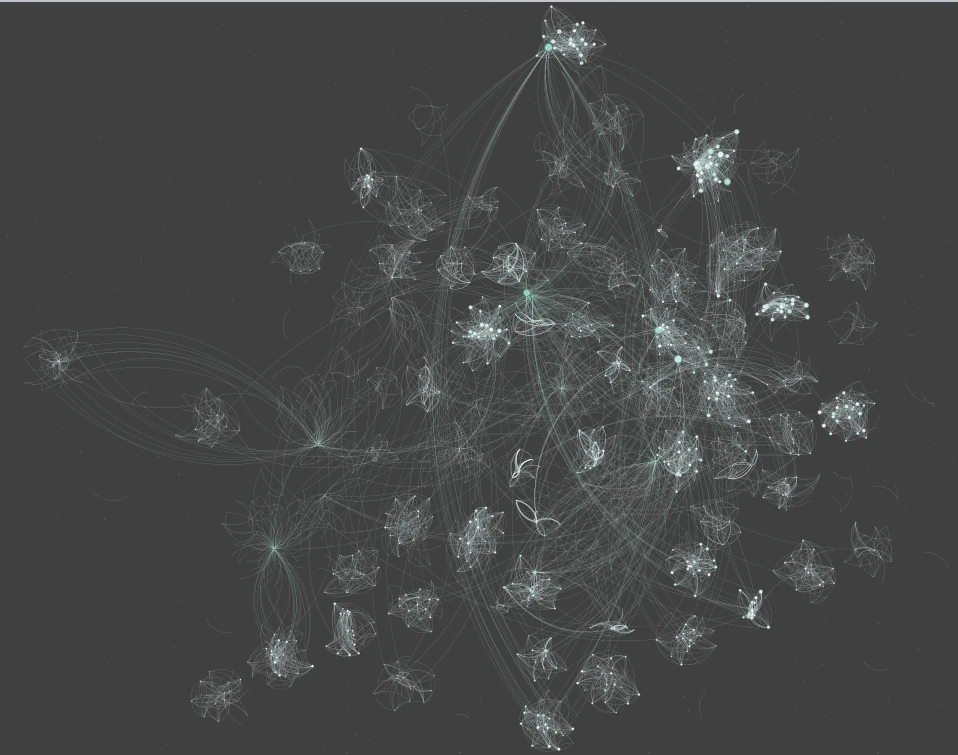

One such category of informal social identity is that of reputation systems. Organizations like Gitcoin and Lens are working to compile and verify users’ disparate online identities into portable social graphs. These systems are useful because they can aggregate informal markers of identity like a username, ownership of a digital collectible, proof of attendance, or even simply control of an ethereum address.

Building reputation as an accumulation of iterative action is a socially intuitive way to establish digital identity—and a more relational component of a locally sovereign web than monolithic state or institution-based identity systems. Immutable blockchains stand both to provide the infrastructure and cultural support for the implementation of these architectures. Because they aren’t controlled by a centralized entity that may someday go away, they are more permanent and portable than any more self-contained identity solution.

A Note on Privacy

While crypto emphasizes privacy as a core value, paradoxically any interaction with most blockchains today are completely open and traceable. Zero-knowledge proofs are an innovation that promise to bring privacy to crypto networks by allowing the validity of a statement to be established without revealing the statement itself. Tools can be built on open infrastructure, but personal data can remain in control of the user and shared only to the extent desired.

This kind of privacy is vital for many of the systems we’re discussing here and, very excitingly, already beginning to be possible. In fact, there are already identity systems, messaging, and blockchain applications experimenting with the implications of zero-knowledge privacy tools.

Digital Hardness

Privacy, combined with digital hardness derived in blockchains, community verification, and social recovery of sovereign accounts could allow us to trust digital information and relationships much more than we do today.

Today formal processes for local representation rely on slow, in-person governance mechanisms. A reliable digital identity structure would make online feedback as real and credible as in-person feedback, and invite more responsive and dynamic governance—for both municipalities and more informal organizations. It is easy to imagine that proof of attendance to neighborhood meetings, accumulated on-chain over time could become an important part of local identity and be used to help trust online actions.

As AI makes everything less believable, systems that rely on interpersonal relationship grounded in a physical place may be the only digital identity systems that prevail.

First Steps

So, if we are to work ourselves iteratively toward ‘hard’ online reputation systems, we should start with the basics. The first step toward aggregated identity is simply somewhere for an identity to accumulate to. User controlled accounts (addresses) are foundational to blockchain architecture, and systems like Ethereum Name Service (ENS) apply human readable naming systems to those accounts. These addresses can hold assets from US dollars to magazine subscriptions and prove legal incorporation of a company.

Compared with the norm of one-account-per-website, such a portable account system makes access more flexible for users while lifting the burden of account management from creators. This infrastructural cornerstone of community computers can be used to manage access to governance forms and other forms of digital collaboration. With more opportunities for direct governance , these tools may start to shift power dynamics in the management of our places.

A More Engaging and Dynamic Governance

DAOs will slowly start to eat the local government model.

We will actually see panarchy implemented, first at “hyperlocal governance” level.

NYU researchers have called this “the piecemeal circumvention of the administrative state.”

Just as the internet blurred lines between traditional media institutions and individuals, new social technologies for empowering local agency and governance are already softening the distinctions between neighborhood Facebook and Nextdoor groups and formal city governance. These tools can support and expand the viability of existing, but limited physical experiments in small-scale sovereignty—ranging from the reclamation of indigenous land tenure to the more playful communities of Užupis and Freetown Christiania.

While determined communities will always find creative ways to establish local agency, community computers can provide an accessible, transferable infrastructure for self-organization that allows these models to spread more widely. A proliferation of more locally capable communities, interconnected by shared organizational infrastructure facilitates the incorporation of local and regional relationships into the kind of broad polycentric structures that Elinor Ostrom and Gandhi envisioned for a healthy society. Compared with fragile top-down structures, this locally emanating organizational superstructure is patterned for resilience.

Pathways To Shared Power

There is a paradoxical push and pull for decision-makers in cities. While municipalities aim to create a great place for their residents, they often exclude them from improvement efforts because the unity of vision and efficiency of central planning is too appealing. In the minds of those bureaucrats who think highly of their ability to plan for the future, there is no safe way to give up their power to plan for others.

Community computers can help bridge this gap between representatives and represented—first by making accounting and decision-making more public. Once on-chain, pathways open for more direct ownership and control to be handed over iteratively.

Digital Structures for Governance of Physical Space

Many digital communities already harness platforms like Github and Canny to allow for simple and collaborative co-creation of functional software and websites. Because of crypto’s account-based foundation, a diverse set of tools of collaboration exist today, ready to be used similarly in our home places. With more trustworthy systems of digital identity, we might be able to make GitHub-style pull requests on planning documents and have our ideas approved with enough community support, bypassing institutional delay.

Voting

Voting is the bedrock of collaborative governance in most modern societies. While digital voting has long loomed as one of the potential unlocks of mature digital identity systems, even in their absence blockchains are enabling novel forms of voting. Prominent on-chain voting tools include Snapshot, Tally, Aragon, and Coordinape.

In the world of decentralized finance, blockchain protocols are often managed with governance by delegation, in the tradition of liquid democracy. Delegated voting power can be revoked or changed in real time, and individuals are free to vote independently if they choose. In contrast to more formally recognized government representatives in our real world communities, this structure allows involved and interested members to gain influence in the governance of their community without as clear of a line drawn between represented and representative.

Conviction voting is another innovation enabled by community computers. In this model votes are continuous and can be changed at any time, but grow stronger in weight over time if they are not changed. The ability for signals and support for initiatives to rebalance over time creates a more active and accountable model of governance than one-time votes on issues, and the consideration of conviction over time provides stability.

These and other exciting new experiments promise to open doors for novel consensus formation in our communities by rounding the hard edges of one-time voting, allowing residents to participate more actively in governance of local issues in real-time.

Participatory Budgeting and Public Goods

Blockchains don’t just serve as trustworthy record keeping infrastructure for identity and voting, they introduce natively digital value transmission. Combined with their transparency and potential for collaboration, they give us a pathway to collectively and directly manage the budgeting and funding mechanisms of our jurisdiction or organization.

Today, some of the most important on-chain organizations (DAOs), such as MakerDAO, are already completely auditable in real-time with governance that happens on-chain, meaning votes are capable of executing their results immediately. In the same way, there is the potential for city budgets to be managed directly and transparently on-chain. For smaller communities willing to experiment, these new tools are available even today. Their experiments can open doorways for larger communities, more burdened by the bureaucracy of yesterday’s organizational infrastructure.

A DAO is a way for people to get together to vote to control a pot of money or a protocol on the blockchain.

— Matt Levine, The Crypto Story

Giving constituents more direct say over where government money is spent is not a new idea. Participatory budgeting is well-loved by advocates of more representative governance, but it is also historically difficult to administer—often introducing the need for more government intermediation instead of less. Community computing can help real-world communities address these organizational hurdles.

If these tools for collective management of public money are properly integrated with local tax and budgeting agencies, citizens could even be given direct power over a certain percentage of their own property tax or sales tax dollars—further engaging citizens in co-creation. Money could be placed in something like a donor-advised fund, except with the local municipality as the sponsoring organization and the citizen as the advisor for its destination. Endaoment is an organization already taking advantage of the opportunity for collective management of money in the world of traditional donor advised funds.

Another experimental mechanism for more participatory financing is that of retroactive public goods funding. In such a system, the value of services provided by an individual or group is estimated and paid for by participants after its implementation. Though not realistic for every endeavor, this structure may push public projects to be more iterative and relational, serving as a possible antidote to unaccountable accumulation of debt that is our habit for large-scale projects today. Over time, this structure can invite individuals and non-government entities to build their own capacity for placemaking, releasing the local government from being the only party responsible for the funding of public goods.

New Funding Mechanisms

Beyond empowering communities to be in more direct relationship with publicly managed money, new on-chain funding infrastructure promises communities more opportunities for direct relationship with the businesses that serve them.

Innovative small businesses have been notoriously difficult to finance with bank-held debt, but had few historical alternatives. A revolution in crowdfunding and crowdlending for thoughtful real estate investment, regenerative farming, and community projects reveals a strong desire for novel funding infrastructure.

Opportunities for more relational local economies don’t end with simple crowdfunding. Use-credit obligations allow businesses to exchange ‘coupons’ for future goods or services for money today, directly with customers. Community supported agriculture (CSA) allows the same type of relationship between farmers and community members. While these are not new concepts, they do stand to be uniquely invigorated by the interoperability, autonomy and verifiability that blockchains offer.

Today, blockchain-based tools like Juicebox provide simple infrastructure for crowdfunding and distributing shared ownership over digital property. Gitcoin Grants Stack allows users to coordinate community-driven grants funding. Clr.fund allows participants to crowdfund public goods with the aid of quadratic funding, where philanthropic individuals or organizations contribute to a matching pool that is dispersed in higher proportion to causes with more individual donors.

Collective Ownership and Action

Collective ownership and stewardship of place has been practiced in healthy communities throughout history, working best when it is strongly supported by culture and tradition. In contrast, individual ownership is often the only legally and culturally supported mode of ownership today.

Though programmable money does allow the possibility of a more quantified and financialized society, it also provides infrastructure for collaborative, common ownership. In fact, tools for shared ownership and action have been core to blockchains since the beginning. It is up to us to use these tools to counter the encroachment of atomizing property modalities upon remaining traditions of mutual support and stewardship.

Recent efforts to revive collaborative ownership structures in more individually focused cultures include models like land banks, community land trusts, and cooperatives. A digital commons for iterating and sharing these structures, supported by community computing, gives earnest communities a turnkey organizational infrastructure complete with identity, voting and financing pathways—interoperable with their neighbors yet flexible enough to iterate over time. Eventually, blockchain-based smart contracts may be recognized as able to convey reliable and trustworthy ownership structures independent of state recognition entirely.

Community Ownership of Public Land

Champions of local sovereignty have the opportunity to integrate long standing traditions of collective land management practiced from Nepal to Mexico with emerging digital commons to mature these practices in their own communities. While today these traditions are strongest in community forestry, their lessons apply more broadly. Large numbers of vacant properties sit idle across America in city-owned land banks, often locked behind the tight control of city-councils. Community computing infrastructure gives cities the tools to have these properties managed directly by local residents.

When integrated with digital identity systems, voting shares in publicly owned lands could be distributed directly to local residents or neighborhood groups. Multisignature smart contracts and other on-chain legal innovations already exist for the cooperative management of sensitive and valuable property and could be applied in this case to collectively control shared resources with transparency and verifiability.

Common Ownership of Housing

Today, volatile housing markets and a crisis of affordability have led to a call for new approaches to housing accessibility in our communities. These calls have been answered by pushes toward shared ownership and collective management—from common land under private housing to collective funding of construction.

While encouraging, these efforts are still sparse and often dependent on professionals with personal skin in the game or dedicated and supportive non-profits. Plug-and-play blockchain infrastructure for such management can make these shared-ownership models more accessible. Prepaid rent vouchers for financing housing (rent-credit obligations) are one strategy that stand to become much simpler for communities to manage on their own.

Such experiments may be appealing first to nonprofits like Habitat for Humanity, who already own groups of homes, but eventually shared ownership could appeal to motivated neighborhood groups or even friend groups. Once the infrastructure for shared housing ownership is established, more mature groups may expand to function like more formal jurisdictions to manage public infrastructure like roads, utilities and internet.

On-chain Tools

Tools for collective governance of shared assets are already being actively used and maintained on-chain. NFTX, is a protocol which allows non-fungible tokens (NFTs) to be deposited in exchange for a share of collectively deposited assets. While used to create more liquid markets today, this infrastructure for collectivizing ownership and action can also be used in our neighborhoods. Tools like Party Protocol are being developed for collaborative governance of shared digital assets. Groups like Partial Common Ownership are exploring blockchain-based structures for ‘plural property’ in the physical world, showing the ability of flexible smart contract systems to aid in experiments with new ownership structures, such as the Harberger tax or Georgist land tax systems.

New Experiments in Knowledge Distribution

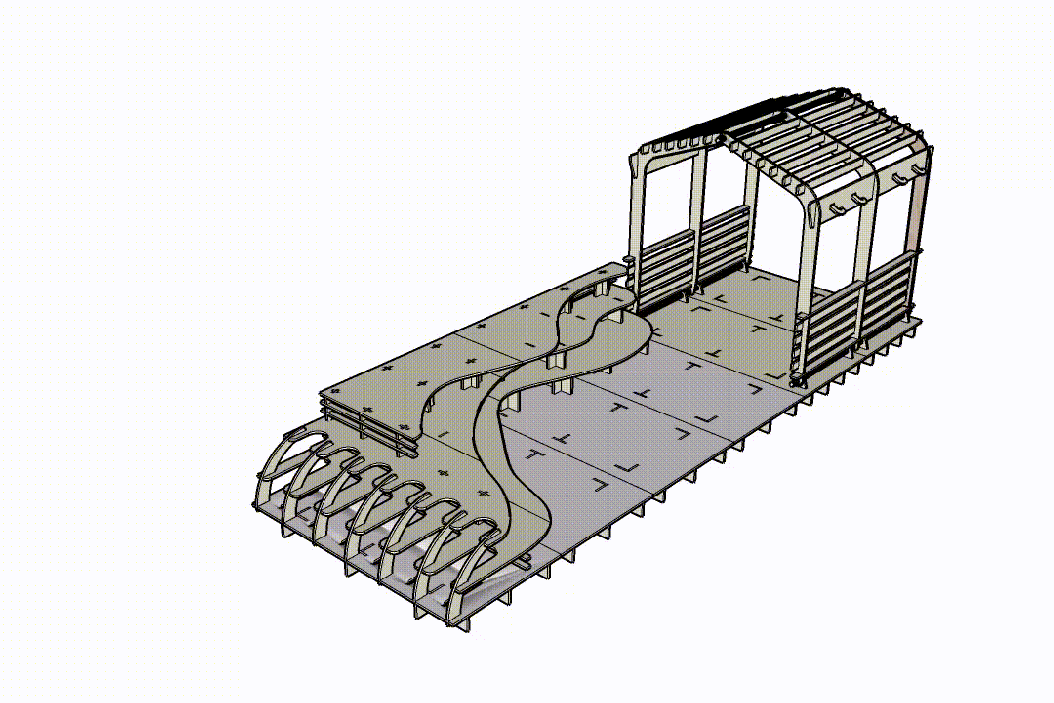

Of course, innovation in collective action and ownership is not limited to physical property. New infrastructure for distributing knowledge and design globally can serve as a valuable resource for empowering the average citizen to take iterative action and make their ideas a reality in their home place. In the tradition of tactical urbanism , this capacity for action can reduce local dependence on outside (sometimes predatory) service providers for cities.

A robust interoperable infrastructure for the distribution and management of digital property already exists to support the world of digital art. Meanwhile, marketplaces and commons for 3D printing, CNC, and more are emerging, but still fragmented.

Marketplaces and payment rails native to crypto networks, made available to local socially-minded entrepreneurs or cooperatives could help to proliferate robust resource libraries for locally empowered placemaking. Participation could be incentivized through on-chain royalties, subscription models or simply networking like-minded communities.

Such libraries and marketplaces could make design and implementation of bus shelters, parks, bike lanes, and even homes much more accessible to the average person—empowering resident-led infrastructure maintenance. With cooperation from local municipalities, approved implementations from these design libraries could reduce the burden of development restrictions on residential and home construction, or even procurement hurdles for cities themselves.

A Note on Hyperfinancialization

In advocating for new forms of ownership, we risk movement towards a kind of hyperfinancialization that only serves technocratic systems of financial control. While I have already written about this elsewhere, it is worth directly addressing the tendency in the crypto community to treat market liquidity as a virtue.

Balaji Srinivasan envisions a world where, “every ideology, everything will have a price, which roughly reflects people’s measure of belief in it.” Today you can already find intimate artwork representing childhood memories available on 24/7 marketplaces. This kind of hyperliquidity of everything—and the resulting hypermobility— objectifies personal relatedness. It works directly against genuine loving care for specific places—the necessary ingredient for sustainable and resilient places. Much more is said about the consequences of the distance that subsuming markets create in the essay It All Turns on Affection by Wendell Berry.

Social Coordination

Beyond physical and digital ownership, blockchains can support broader social coordination as well. One example discussed by Vitalik Buterin is the decentralized coordination of a conference. In this example, like-minded people can place a deposit into a smart contract along with a preference for a location. Once a threshold of deposits with a matching location is met, money would be placed in a treasury and collectively managed by the participants to coordinate the conference. Such a mechanism could catalyze local neighborhood events or crowdfunded civic projects, similar to existing organizations like Ioby. This kind of opt-in funding helps present a middle way between ‘messy’ decentralized dialogue-based coordination, and ‘speed-optimized’ centralized control that modern municipal governments often default to.

Money

Finally, we cannot discuss cryptocurrency without discussing its role as money. The shape of our economies dictates so much of institutional and social form that money cannot be ignored when considering the health of physical communities.

Universal Money

Since Bitcoin arrived in 2009, there have been many concurrent blockchain-based experiments in what a state-independent universal money can be, including Ethereum (serving as a specific currency for blockspace), DAI (a collateral-backed currency that seeks to peg itself to the US Dollar), and RAI (an experimental stable asset without a peg at all). Demand for global money is not going away, and many interesting experiments with this goal are still developing.

Of course, states themselves are exploring how they might manage their own digital currencies. Today most dollars are created by local banks, and so it follows that new experiments in banks issuing their own money on-chain are consequential for our monetary system. One such experiment, a consortium of banks called USDF, proposes to produce an interoperable money derived from deposits in its member banks. This, and other experiments, may provide ‘state approved’ alternatives to central-bank-issued money.

Local Money

Beyond the pursuit of universal or national money, there is a long history of modern (and premodern) local currencies that becomes increasingly relevant as interoperable, trustworthy community computing systems mature.

Local currencies aim to foster economic relationship within a geographic area, with motivations from building economic mindfulness to steadying local economies in times of national instability. Today many communities with a desire for more relational and less abstract economies, treating money as a social tool, remain committed to sustaining and maturing local currencies across the world.

As many blockchain-based experiments in money are working toward a universal money, the infrastructure for digitally native and composable money enabled by community computing protocols can also help build confidence and capability for formation and maintenance of more locally sovereign financial systems. While local currencies have often been considered siloed novelties, the native composability of blockchains can help local currencies build more direct connections to regional and global economies when helpful, maturing their reach and usability.

With more capable tools for local money, municipalities have the opportunity to lead a push away from precarious international monetary policy, even if they begin as complementary experiments rather than real thrusts for local monetary sovereignty.

Obligation-Clearing and Mutual Credit

Understood most broadly, local currencies are attempts at building sustainable, locally coherent financial systems without outside dependencies. A simple step in this direction is obligation-clearing (credit offset), where economic relationships are mapped and account balances between participating parties settle at the end of an established term, often per month. The beauty of this system is that it is not necessary to alter economic behavior in order to significantly reduce necessary cash in a sufficiently-connected economic map. While this may not occur to you as exciting, late invoice payments can meaningfully disrupt the operations of small businesses.

Participants mutually agree to allow a certain amount of value exchange to be settled using an accounting unit internal to the network… The network, through the aggregate commitments of all of its members, is effectively providing its own money supply.

Mutual credit expands this concept and allows participants in such systems to extend credit to each other beyond the period of settlement. Two such systems in the real world today are the Sardex system in Sardinia and Switzerland’s WIR Bank. WIR Bank has been operating since the Great Depression and currently facilitates around a billion euros of trade per year without money changing hands.

One study shows that the Sardex mutual credit system reduces internal debt for the network (and thus the need for cash) by approximately 25% when obligation-clearing is used by itself and by 50% when it is used alongside mutual credit.

Healthy mutual credit systems foster an economy necessarily embedded in relationship, scaling and shifting within the limits of endogenous reciprocity, like a self-sufficient terrarium. They do not attempt to be universally available money or a long-term store of value, but instead serve the needs of users in a specific place and time, replacing the invisible negative externalities inherent in today's boom and bust monetary systems with positive externalities present in mutual relationship.

By reducing the need for individuals and local firms to carry and spend outside money, these systems can be used to make local economic relationships less dependent on fragile banking systems and commercial banks, even while denominating their value in a national currency.

Distributing Monetary Sovereignty

While obligation-clearing is traditionally practiced only in informal relationship between friends and family or formal arrangements among banks, new experiments on blockchains and other digital ledgers are making such credit offset accessible to wider categories of communities.

Mapping and balancing economic relationships on-chain can help communities understand the shape of their existing economy, build more healthy economic loops, and more quickly stand up mutual credit systems of their own. Credit Commons Society is working toward such a system of interoperable sovereign money.

Historically, mutual credit systems have needed a trusted central operator to clear credit, but it is possible these responsibilities can be delegated to autonomous and transparent smart-contracts and managed through on-chain governance. Overall, DAO structures may help with governance of local currency, including visibility and management of who is able to originate, accept and spend the currency.

The use of community computing architectures to engage in more collective and localized sovereign control of monetary systems is more than theoretical. Community Inclusion Currencies (CICs) like Sarafu Network, are real-world applications of highly-localized credit offset, giving people a way to exchange goods and services and incubate projects and businesses without relying on scarce national currency and volatile markets. Many other dedicated organizations are working towards these ends, including, Circles and Mutual Credit Services. Cycles is a blockchain-based system working to build on-chain infrastructure to support mutual credit systems to the benefit small communities.

Where Does That Lead Us?

Taken together, these budding tools for maturing modes of local relatedness provide a pathway to balancing agency and limits over generations, a dialectic equilibrium vital to the health of our neighborhoods, cities, and society.

Instead of relying on the rigid imposition of extrinsic institutional structures, equipped communities can self-regulate against patterns of overconsumption and exploitation by rooting their economic and organizational structures in empathy for one another and their home places. The cultivation of these locally derived placemaking traditions safeguards the vitality of our communities, not just in the present but for generations to come.

How can we get there? Not by abandoning our homes to flee to new communities, nor in the unlikely prospect of healing our institutions from within. Instead, the answer lies in a long-term commitment to our places and a willingness to engage with new tools to build a sustained and vibrant community memory.

A memento for this essay can be found

here.