5

Tools

Rooting Computing in Place & Relationship

Our tools and technologies amplify our habits of relating to each other, our places, our organizational systems, and even time. More collaborative computing architectures can help us shed the prosthesis of institutional control and rebuild the locally-derived competency necessary to steward our places through generations.

Personal Computers unleashed unimaginable levels of sovereignty & interoperability for people.

Community Computers will do the same for groups.

A blockchain is just a Community Computer.

A healthy society is built on relationship, between people and to their home places over time. Our tools can either support or undermine this delicate balance.

Technology in Place

The internet has been the defining tool of the past century. While it appears today as a force of abstraction and disembodiment, controlled by a handful of corporations—we often forget that the first versions of the public internet originated in local interpersonal relationship.

Early bulletin board systems (BBS) were hosted in members' homes, many of whom also met in person regularly. The first BBS was called ‘Community Memory’, a remarkably appropriate descriptor of what we have been discussing. Networks of BBSs like Fidonet even created protocols for interrelation of small communities notably similar to the polycentric organizational structures we discussed in Chapter 2.

For Internet users today, there is more to the BBS story than mere nostalgia. As our online lives are channeled through an ever-smaller number of service providers, reflecting on the long-forgotten dial-up era can open our eyes to the value of diversity and local control.

A return to technologies that help ground us in community and place may be the pathway back to both a more human internet and more sustainable places with coherent community memory.

EF Schumacher and Ivan Illich were already thinking about these ‘appropriate technologies’ and ‘tools for conviviality’ in the 1970s. Ongoing small-scale experiments in place-based relationality like Appropedia have continued to allow the curious to scratch an itch for local sovereignty—but the time is now right for a broader revolution in our local placemaking.

Crypto, In Context

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence promise broad societal changes—but despite its skeptics, the category of emerging technologies that includes the terms ‘crypto’, ‘public ledgers’, blockchains, and ‘web3’ may be opening the most exciting new pathways for distributing (instead of consolidating) power toward more resilient home places, in the lineage of BBSs.

A Note on Terms

In the discussion of these technologies, I’ll try to use plain (if uncommon) language instead of terms like ‘crypto’, not only for the sake of those who are unfamiliar with the language of ‘crypto twitter’ but also because many in the field have been made cynics by recent failures of its culture to produce worthwhile tools. Thinking in terms of ‘community computing’ can help us lift our collective gaze to what is possible with these technologies beyond the many failures we see today.

This essay seeks to put these emerging tools for collaboration in their historical and social context. It won’t try to form some all-encompassing survey of the many corners of crypto, but instead will identify some of its core cultural principles as they relate to affectionate economies, rooted in their place. The concluding piece in the series will more deeply explore near term applications in our physical communities.

Blockchains are not personal-computing operating systems; they are social systems — Vitalik Buterin

Societal Change Spurred by Technology

Just as the printing press distributed the power of knowledge once centralized in religious institutions and the internet distributed the power of voice once centralized in media institutions, new tools for community computing have the potential to distribute the power of money and other systems of value management now with high degrees of centralized risk. One federal bank deciding the fate of the world economy is not how value worked historically, and it is likely not a healthy or permanent feature of our global economic system. These tools go far beyond money as well, with the possibility to reclaim systems of maintaining our places, independent of helicopter states.

Cycles of Centralization and Decentralization

The internet isn’t the first technology to challenge the legitimacy of presiding institutions (or to give way to new institutions). Keen observers have noticed a common cycle of decentralization and re-centralization associated with social technological leaps throughout history. In this pattern, technologies that enable new ways of coordinating catch on quickly at the interpersonal level, injecting energy, engagement, and even solidarity into organizational structures.

Incumbent (and more centralized) institutions struggle to keep pace with these emerging organic structures, so the process is naturally decentralizing. As new and remade institutions attempt to stabilize and scale the movement, process begins to supersede local sensitivity. This ’efficient’ institution is again unable to represent the diversity of its constituents, and the organizational structure begins to feel the weight of its overextended borders. When the time is right, the resulting structural weakness is often exposed and challenged by new social technologies or other catalysts for change.

While this model fits the evolution of the internet itself, some other examples of social technologies that were catalysts for cultural phase transition include:

- Cooperative, common-pool irrigation, which expanded agricultural capabilities

- Greek alphabets, which led to broader trade and language dissemination

- The printing press, which greatly expanded publicly available written material

- Templates for cities and market towns, which led to federations and city-states

- Double entry bookkeeping, which greatly “increased the power, leverage, velocity, composability and granularity of money”

These thoughts are based on some fantastic resources from Ethan Buchman, Jon Hillis, and Josh Rosenthal (among others). I encourage you to dig into what they have to say if you have any interest.

Physical Changes by Digital Means

Of course, it’s not just culture and institutions that are changed by new tools. From the birth of agriculture to the industrial revolution and the advent of the automobile, our technologies have always influenced our places. And so, as an increasing number of people spend more time online than being physically present, the internet represents not just a retreat from the physical, but a strong influence on the shape of our places. Today we have seen greater internet connectivity move less dense urban regions towards greater physical and local-social cohesion over time and remote work change our relationship with in-person coordination altogether.

Understanding how the internet has and might impact our physical world, we can also dream how we can make physical communities more resilient with a more empowered internet. In particular, we can look forward to how new internet-based tools will impact collective coordination by more deeply engaging and empowering small groups of people to shape their immediate surroundings.

New Tools for Collaborative Coordination

Relational modes of sharing and transferring value, like cooperatives, are often more organizationally burdensome today than conventional market-based economies. Time and energy spent cultivating personal and economic relationship is simply more difficult in a society that has replaced interpersonal trust with Amazon reviews.

Elinor Ostrom recognized the ’tragedy of the commons’ in common pool resources to often be a problem of coordination, saying, “All we had to do was to introduce the possibility of face-to-face communication, and that allowed [groups] to increase cooperation.” When allowed to cooperate to design systems for managing common pool resources, local people often outperform institutional intervention. And so, new tools for collaborative coordination can simplify the path toward local capacity for interrelation and mutual affection.

It’s not that people are incapable of collaboration, it’s just that most of us lack tools

Despite the promise of being more effective and empowering, it is crucial that new tools for the coordination of self sovereign communities be sufficiently learnable by a broad enough demographic, otherwise they risk becoming infrastructure for the same kind of intermediaries we rely on today to coordinate our economies. If made accessible, community computers and other collaborative technologies can mature knowledge sharing aspirations present in organizations like makerspaces and cooperatives to help them compete with legacy economic relationships.

We must make it possible for the average layperson to be able to change and adapt software for their own needs; for them to experience creating software not like a professional chef, but a home cook.

— Jacky Zhao, Communal Computing Networks

Such digital coordination can be fun and intuitive—and has yielded collaborative design and production of everything from industrial machinery and scientific processes to frog houses and park benches. Supported by collaborative technologies, digital commons can enable key functions of physical placemaking—making home-building and transportation infrastructure more relational, spontaneous, and fun.

Defining an ‘Empowered Internet’

People seeking refuge from the industrial scale and surveillance of the modern internet are advocating for a retreat to what is being called the ‘cozy web’. The concept represents a more private and interpersonal oasis of digital relatedness.

This desire for online autonomy isn't new. Privacy enabling cryptography has been powering our relationships on the internet since its beginning (and before). Cypherpunks were fighting for digital privacy and freedom already in the 90s, and their efforts helped pave the way for digital currency systems independent of state control. This movement began with Bitcoin in 2008 and today is called crypto. Bitcoin first was an attempt to subvert institutional power, but crypto has become home to a much wider range of ideologies.

Cypherpunk philosophy is fundamentally about … creat[ing] a world that better preserves the autonomy of the individual, and cryptoeconomics is to some extent an extension of that, except this time protecting the safety and liveness of complex systems of coordination and collaboration, rather than simply the integrity and confidentiality of private messages.

— Vitalik Buterin, A Proof of Stake Design Philosophy

Caveats and Uncertainties

Ironically, much of what has been written about the ability of these technologies to build local agency has come from the many venture capitalists (a different kind of large institution) looking to make money from their salesmanship rather than an ability to build meaningful new tools. This kind of gold rush in the world of crypto has attracted some unsavory characters and resulted in often extremely negative public opinions, many well-founded.

What's more, the disruptive and open nature of these technologies means that the development of these social systems may only continue in the shadows as regulatory oversight becomes burdensome. In the end, these systems may only provide an escape from the most oppressive of states rather than a broad social movement that moves small communities in all places forward.

Still, I hope to help you look beyond the opportunists and pessimism to see that there is something material and substantial about these emerging technologies that can help us claim more agency from centralizing forces that have eroded community health and local generational memory over the past century.

Despite these uncertainties, community computers are already being used to improve places in small ways today. We’ll get into some specific examples in our final chapter, but first let's engage with the spirit of the budding technological tradition we’re discussing.

Digital Sovereignty and Resilience

Digital sovereignty is perhaps the most basic pursuit of these technologies. What began as a retreat from state-controlled money, has become a pursuit of freedom from broader dependencies. Vitalik Buterin, the inventor of the prominent crypto protocol Ethereum, has famously stated his invention of the shared computing platform was, in part, a response to having one of his favorite video games changed without notice or input.

I happily played World of Warcraft during 2007-2010, but one day Blizzard removed the damage component from my beloved warlock’s Siphon Life spell. I cried myself to sleep, and on that day I realized what horrors centralized services can bring. I soon decided to quit.

These principles of self-determination are also tightly tied with privacy. A lack of privacy can result in altered behavior—either through fearful self-censorship or due to intervention by surveilling institutions (of which the internet has a long tradition of).

Distributed systems that grant sovereignty and privacy by default make surveillance harder for states. What institutions may give up in control, though, they gain in resilience by empowering citizens to engage more deeply in maintaining their own tools and places.

Empowered Participation Through Direct Ownership

Throughout most of human history, people were inescapably intertwined with their home place and their neighbors. Today the path of least resistance is outsourcing all home and placemaking activities to professionals in exchange for money. Even local governments often use outside consultants to accomplish their work. As we’ve discussed, this prosthesis dampens our sensitivity to the people and places around us, and erodes the health of our society.

Community computing networks allow people to build tools to own and actively participate in the making of their community rather than paying a ‘specialist’ outside the community. This principle began with Bitcoin’s approach to money, but now this infrastructure is poised to provide a more relational and engaging path to community management more broadly—in support of collaborative processes like collective budgeting and mapping of potholes.

Composability & Openness

For many potential uses of community computing, the question is often asked pointedly, ‘why does this need to be on a blockchain?’ One of those reasons is that distributed protocols lend composability. This means that infrastructure natively brings tools in relationship. In the world of Ethereum, users don’t create a user login for individual applications, but instead carry their universal accounts with them. This not only simplifies user experience but integrates available payment, identity, and voting solutions for any application on the network.

These open maps of relationships, when combined with appropriate privacy considerations, can produce new kinds of collaborative, synergistic relationships that are impossible to achieve in a world of intellectual proprietarianism.

Blockchains not only provide the technical infrastructure for more collaborative technology, they also carry the cooperative ethos of open source digital projects that has been thriving for years, with The Cathedral and the Bazaar as the seminal ’theological’ work. Many of its 19 lessons for creating good open source software are also cultural cornerstones in the world of crypto, including making ‘users’ into collaborators, and the free sharing of code.

In order to see spontaneous and creative growth, we need credibly neutral platforms on which to build, with low barriers for creation, something that you can trust to build on. There are parallels to cities, where people know they are dependent on developers and the city, who may change rules … and so there is no incentive for spontaneous creativity.

Social Scalability

Many of the failures of today's institutions are not necessarily because they are by some definition too large but because the technology and organizational structures they are built on can no longer remain sensitive to interpersonal relationship at their current scale. Nick Szabo pioneered the argument that blockchains allow shared endeavors (what he calls institutions) to scale beyond what is typically locally and socially viable through traditional means, calling this social scalability.

The number and variety of people who can successfully participate in an online institution is far less often restricted by the objective limits of computers and networks than it is by limitations of mind and institution that have not yet been sufficiently redesigned or further evolved to take advantage of those technological improvements.

Blockchains can remake standards of relating at scale to more appropriately integrate local sovereignty. Their infrastructure is not mediated by any authority so the network is open to anyone by default, without need for social context or permission. Most tools built on blockchains are open source, so their code can be reused (or ‘forked’) by future communities. These cultural foundations support the possibility for ‘exit’, allowing members to depart and establish new communities when disagreements or divergences arise. The ability to access, and if necessary, exit crypto networks and communities results in a dynamic, spontaneous and iterative ecosystem, all key factors in fostering agency.

A Note on Digital Agency

The erosion of opportunities for building agency in the physical world has led some to pursue digital-first sovereignty, even going so far as to suggest network states: political entities whose members are digitally and philosophically united, though physically dispersed. I acknowledge that sometimes digital agency is the only form of agency people have available, however I am doubtful that this approach can lead to healthy communities over generations because it is not grounded in place.

Digital tools can be powerful for scratching our natural itch for agency, but anchoring them in a physical reality (as makerspaces do) helps to avoid manipulation by and dependency on outside actors, as we are now subjected to in most internet communities. And so, grassroots physical subversions of presiding economic and political structures, such as spontaneous scrap recycling in Agbogbloshie, are more potent than digital ones that hope to retroactively embody themselves.

A Note on Infrastructure

While the internet itself still has a great deal of dependence on centrally managed physical infrastructure today, physical peer-to-peer infrastructure such as mesh networks can and must be a necessary synergistic companion to the kinds of tools for decentralized (digital) organizational infrastructure discussed in this chapter. We cannot have communities with agency if they do not have agency over their tools for organization, as the tools themselves play a part in imparting agency.

Cultural Diversity in Crypto

While open systems can create the right conditions for agency, there is the tendency in the world of crypto to favor censorship resistance and minimized governance over social flexibility to achieve incorruptibility. The ability to make open, general purpose, permanent and uncensorable tools is important, but so is the ability to have stewardable, socially responsive technologies. In her research, Elinor Ostrom found that locally maintained systems often work better than ‘superior’ engineered solutions because the former are maintained with active engagement. Permanent systems designed without the need for maintenance are susceptible to disuse and disengagement. If the goal is to improve systems of self-organization, then we must welcome social process.

This tension between the universal accessibility of formal and rigid systems and the invitation to local spontaneous engagement potentiated by more informal systems has been the subject of debates in the communities of the Ethereum and Cosmos blockchains.

Ethereum is designed to function best as an immutable and permanent source of ‘universal’ truth. This helps make tools composable, interoperable, and free of dependencies—over time building a robust web of resilient yet accessible infrastructure.

Recently, we’ve invented a new way to create hardness: blockchains. Using an elegant combination of cryptography, networked software, and incentives, we are able to create software and digital records that have a degree of permanence.

If we aim to use technologies like blockchains as an alternative or companion to large institutions, we should be careful not make them too inflexible in the name of stability. Social systems are complex and we cannot treat our expectations for them as rules as hard as the setting of the sun.

Healthy natural systems have mechanisms for unwinding or relieving built up pressure, and so must we in our technological systems. Such architectures may come from communities like Cosmos (and Celestia), which seek to provide local sovereignty at the community level, with more degrees of freedom in designing how to build and maintain social consensus—but also with more responsibility for maintaining critical infrastructure.

Together, these new foundations of community computing can help forge pathways of polycentric, cosmolocal agency propagation toward strong local resilience and community memory over generations—where specific communities are empowered to maintain locally sensitive infrastructure alongside more universally available and credibly neutral rails for sharing knowledge.

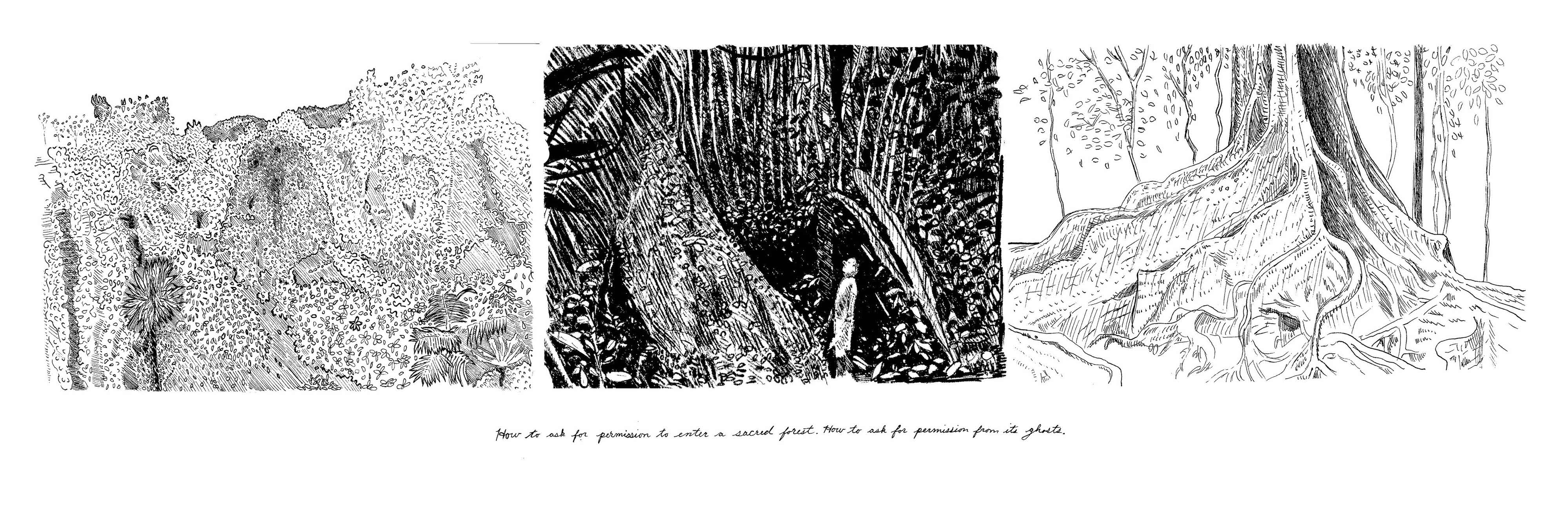

A memento for this essay can be found

here.