3

Limits

Derived in Affectionate Relationship to Each Other and our Places

As globalized economies accumulate hidden existential debts, institutions seeking to control for risk instead reinforce our trajectory. Affectionate and empathetic relationship with the people and places around us can help more effectively build resilience and diffuse these risks.

Outside Dependencies, Unknown Limits

As our economic systems continue to globalize and decouple from local relationship, our communities increase their dependence on outside resources. This dependence erodes local agency and leaves the consequences of our actions to accumulate out of sight. When some communities consume beyond their local capacity, others are compelled to produce beyond theirs. This imbalance embeds pathways of exploitation into our economic system, often with our ‘best’ places becoming the most dependent on this exploitation.

In the last 100 yrs, California’s Central Valley has overdrawn the aquifer (extracted more water than has been replenished with rain or snow) by more than 122 million acre-feet, or 45 trillion gallons. As much as 80% of this water goes to agriculture.

Farmers in the drier areas of the valley rely almost exclusively on water pumped from the aquifer instead of river water. The ground in these areas has sunken by as much as 30 feet in the last 50 years and continues to drop a foot per year— Sam Knowlton · Jan 5, 2023

Sadly, in a consumption-focused context, where places are seen as products, there are progressively fewer loving stewards and more only-economically-present landholders. The average globally-minded manufacturer exists in its place so long as it remains financially prudent, ready to move on to greener pastures even when they themselves are responsible for degrading those pastures. As a result, we have less and less personal relationship to the food and products that sustain us, and so are not faced with the implications of our consumption.

Such impersonal economies have strong incentives (both explicit and implicit) against managing their risks. Altering a supply chain is inconvenient and expensive, while internalizing the consequences of such abstract patterns of consumption is difficult. This inability to metabolize sorrow from a distance is known as psychic numbing, and is the reason why globalized economies trend towards local decay over time. Without the ability to account for accumulating problems locally, like toxins in water, these consequences have cascaded into the broader existential weight of climate change and increasing cancer rates.

‘Growth’ and Deferred Maintenance

The consequences of our economic relationships aren’t only pushed out of sight but also veiled in assumptions about a future we never bother to imagine arriving. We do this every day by applying synthetic fertilizers despite their deterioration of the soil or by using fossil fuels despite the near-term inevitability of their exhaustion. These precarious trajectories are often explained away because of assumptions about future growth or ’technological progress’.

As we saw in the history of German forestry, however, modes of placemaking optimized for growth make us indebted to the future with no guarantees the debt can be paid. Over time, management disconnected from local places tends toward an insidious burden of deferred maintenance and unfinished work imposed on communities with no means of course correcting the bureaucracy in charge.

In the making of our places, state and federal transportation authorities are happy to subsidize new construction to grow their tax-base when they aren’t responsible for maintenance. Politicians are glad to put their name behind flashy projects promising growth if it means they get reelected. This burden of maintenance grows with each new development, necessitating even more growth to keep existing infrastructure functional.

Once a complex society develops the vulnerabilities of declining marginal returns, collapse may merely require sufficient passage of time to render probable the occurrence of an insurmountable calamity.

— Joseph Tainter, The Collapse of Complex Societies

Local people themselves will remain on the hook for the generational effects on the land and people’s health of growth-beyond-means long after the consultants are gone. Lost lives and abandoned communities can’t be remedied by more federal dollars, but local people won’t know how to get out of these situations if they weren't a part of getting there. Building locally derived traditions of organization, then, is vital to the survival of our home places.

Black Swans

In addition to decline through deferred maintenance, economies of scale also carry the risks of less predictable but more catastrophic outcomes. The relatively few fulcrums in large-scale systems mean there are fewer mechanisms for proprioception. This can lead to violent collapses or unwinding events, as unaccounted-for externalities compound into unpredictable but very real consequences.

Nassim Taleb has become well known for cautioning against these risks in recent decades, but this phenomenon is not new. Ibn Khaldun described non-agentic dependence on outside resources as a precursor to societal collapse as early as the 1300s in one of the very first sociological texts. As we prepare to outsource even more of our faculties to artificial intelligence, the existential risks of total loss of agency are top of mind these days.

Institutions Reinforce the Accumulation of Risk

To account for the compounding externalities and existential risks of our abstract economics, institutions seek to conjure limits for us, inducing their own collection of problems. Their resulting impositions are vulnerable to regulatory capture, arbitrage, and pushback. And so, we end up with certified ‘grass-fed’ beef where the cattle are fed grass pellets in a feedlot.

In search of defensible limits with predictable outcomes, regulators employ tools of statistical analysis—but these calculations perpetuate the accumulation of risk both through their oversimplification of complex systems and their exclusion of local people.

In fact, the lack of local sensitivity in the implementation of regulatory limits often destabilizes the communities institutions intend to protect. In Sri Lanka, for example, a total ban on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides recently produced unintended food insecurity—sharpening inflation and political unrest.

Bureaucratic regulation itself generates further complexity and costs. As regulations are issued and taxes established, those who are regulated or taxed seek loopholes and lawmakers strive to close these. A competitive spiral of loophole discovery and closure unfolds, with complexity continuously increasing.

The Ecological Insufficiency of Institutional Limits

It is not just social rejection of institutionally imposed limits that reduce their viability, as was the case in Sri Lanka. Imposing outside control over local systems can compound real ecological consequences in ways that may not be immediately apparent to the institutions that rendered them.

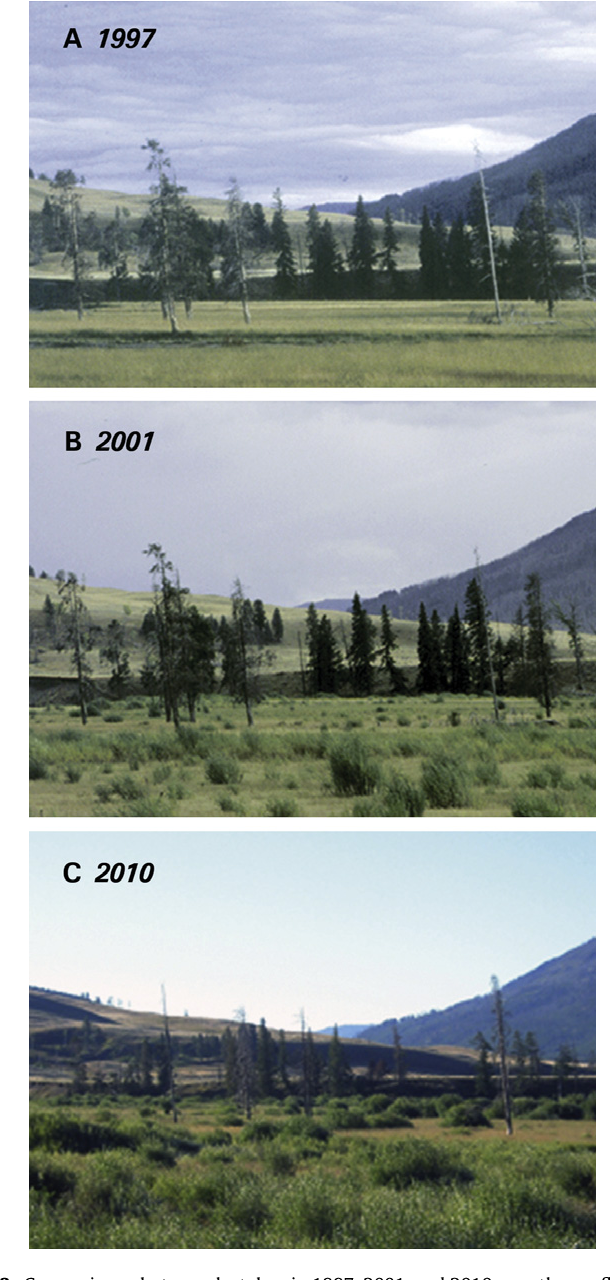

One such example is the classic story of the removal and reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park. Wolves were once the top predator in the ecosystem, but by the 1920s they had been effectively exterminated due to federal and state-sponsored predator control programs aiming to protect ’economically important’ livestock and game populations.

It was not until the 1960s that the resulting ecological imbalance became evident. Elk became overpopulated, overgrazing willow and aspen stands with ripple effects throughout the region, affecting other species and leading to a substantial decrease in biodiversity.

After decades of debate, the effort to reintroduce wolves into Yellowstone began in 1995. This simple step had a cascade effect to the benefit of the entire local ecosystem. Wolves began to keep the elk population in check, allowing vegetation to recover. The recovery of willow stands provided more habitats for beavers, whose dams create habitats for other species.

Despite the good result, the resource and time intensive process necessary simply to return to what were naturally sustainable ecologies should serve as a warning against the kind of overzealous institutional influence our home places rely on today.

Limits Derived in Empathetic Relationship

More sensitive local organizational structures can remedy this tendency of industrial economies to produce existential risk. Instead of accumulating externalities, these structures match inputs to outputs in cyclic patterns that conserve energy and reduce external impact. Natural systems build health—not in their accumulation of resources but in the quality of active and sustainable relationships.

A sustainable system, maximizes cyclic flows. It is fair and just reciprocal exchange of materials and energy that maintains and ensures the survival of the whole.

— Mae-Wan Ho, Circular Thermodynamics of Organisms and Sustainable Systems

While our familiar linear economies hasten destruction as they scale, the nested reciprocal cycles of healthy forests build resilience with scale and complexity. By embracing locally coherent, non-dissipative economic systems, we can develop more sustainable communities that also support broader organizational structures.

Iteration is Catastrophe’s Antidote

Relational organizational structures, with high degrees of local sovereignty and reciprocity, create iteratively adaptive living places attuned to their local environment. This rhythm is more compatible with social and ecological abilities to digest change than our current model of build, rot, replace communities.

An upside to decentralizing food production is that less goes to waste. The same neighborhood can be fed with less inputs and practically no fossil energy thru a few community gardens + backyard gardens and a local farm or two. And the labor to do it is there.

— ryolithica · Dec 4, 2021

Modern growth-focused methods of placemaking defer debt to the future, leading to destabilizing boom and bust cycles. This is seen in what has become the norm for master-planned communities, where thousands of shiny new homes are built all at the same time. While these communities often start as attractive places to live, over time, they face challenges as infrastructure ages, design trends change, and initial amenities become outdated. Natural ecologies, rich in nested cyclic patterns, instead have a less precarious relationship with time.

For true architecture grows out of the organic development of a shell around a group of people. Such building growth is like the growth of a child and of man.

— Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Mouldiness Manifesto Against Rationalism In Architecture

Next we will explore a generational way of thinking about our home places, taking natural ecologies as an example. After that discussion, we will get into specific technologies that may aid us in maintaining these more sustainable organizational structures.

A memento for this essay can be found

here.