2

Agency

Derived in Affectionate Relationship to Each Other and our Places

Life-giving agency must be established through the kind of spontaneous, trust-filled relationship that distant institutions are incapable of. Innovative organizational structures, in rhythm with natural ecologies, can scaffold these relationships into a more resilient organizational mycelium in support of our home places.

A form of government that is not the result of a long sequence of shared experiences, efforts, and endeavors can never take root.

Distance and (Lack of) Trust

The story told is that monolithic institutions are necessary because there are no good alternatives. In such a complex world, how else could we stabilize fragile modern economies other than through rational analysis and precise engineering by well-credentialed professionals?

It is clear, though, that trust in our institutions (and each other) is unsustainably low. Our society doesn’t feel particularly stable, nor are our externalities well-accounted for. And so, in recent decades, we have reason to doubt the proposition that predict-and-provide modes of planning can stabilize and provision livable places.

For large-scale organizational structures to produce a sense of shared societal trust, the breadth of their scope must be balanced by a reverence for local agency. Our systems of government have become incomprehensible to us precisely because they extend us no trust and leave no room for dialogue. Thankfully, effective systems of affectionate and collaborative placemaking are emerging as alternatives to the escalation of intractable externalities and concentration of power.

Established planning practice has tended to follow an outmoded early industrial model. It was based upon a hierarchical “top-down” command-and-control paradigm, leading to predict-and-provide planning. This model does not sufficiently reflect the kind of scientific problem a city poses, because the model ignores the tremendous physical and social complexity of successful urban fabric.

— Favelas and Social Housing: The Urbanism of Self-Organization

Proximity and Congruity

Management-at-a-distance has yielded institutions that fumblingly mold local places into the limited shapes they’re capable of producing, often incongruous with local biophysical reality. And, while local decision-making isn’t a panacea, it does not unduly pursue omniscience with the same hubris as ‘objective’ data-driven decision-making models do. Planning at scale just isn’t the capable scientific exercise central planners think it to be. Instead, metabolizing information from places with distinct local realities expends high levels of organizational energy and yields often unusably aggregated observations. This problem was the thrust of FA Hayek’s seminal work, The Use of Knowledge in Society.

The sort of knowledge with which I have been concerned is knowledge of the kind which by its nature cannot enter into statistics and therefore cannot be conveyed to any central authority in statistical form. The statistics which such a central authority would have to use would have to be arrived at precisely by abstracting from minor differences between the things, by lumping together… in a way which may be very significant for the specific decision.

— FA Hayek, The Use of Knowledge in Society

Overestimating Rationality

A social theory called the Garbage Can Model describes the messy reality of organizational decision-making at scale. This model suggests that, despite their intentions, groups of people don’t typically make decisions by agreeing on a problem, developing a perfect understanding of all the data, then picking the best-fitting solution. Instead, decision-makers most often decide on one of a few solutions that happen to be available at the time and then work backward toward a logical-sounding justification for that solution.

Problems and solutions and individuals and so on are mixed in the garbage can of a choice by their temporal simultaneity, not by their causal linkages. What we persistently observe is that organizations announce solutions to problems that don't have anything to do with the problems, but happen to be solutions that are around at that time.

Overestimating Capability

The planning fallacy is a related mental model that describes the tendency of individuals and institutions to underestimate the time, costs, and risks associated with completing a task, often despite past experiences. While those involved may blame this poor judgment on a basic human tendency for optimism, the phenomenon is also likely related to professionals who believe themselves more capable than the population they are planning for—no matter the local intricacies (and, of course, unrelated to the influence and money that might flow through them). No matter the cause, overconfidence at such a scale can lead to more impactful externalities than are possible with more distributed models of placemaking.

One of the most infamous examples of large institutions' tendency to underestimate costs is the Big Dig, a large highway project in Boston designed to reroute I-93 out of the core of downtown. Ironically, the decision for the highway to be there in the first place was a result of prioritizing central planning over-sensitivity to local neighborhoods.

Originally set for completion in 1998 at an estimated cost of $7.4 billion, the project instead stretched on nearly a decade longer and cost over $21.5 billion (adjusted for inflation), making it the most expensive highway project in the history of the United States. In addition to delays and overrun costs, the project was mired with criminal charges and even a death.

While big plans often have big societal effects, they aren’t always what we intend. Even when our grand plans produce more efficient infrastructure, Jevons Paradox shows us that efficiency can yield unforeseen increases in demand and in turn, overall resource use. This induced demand is well-studied in city planning, where widening roads often simply invites more traffic rather than solving traffic problems.

Legibility and Responsiveness

Formalized organizational structures don’t just overestimate their competency, they also reshape places (and people) in their image for the purpose of predictability and legibility. This concept is explored in James C. Scott's fantastic book, Seeing Like a State, looking at German forestry management practices in the early 19th century.

The utopian, immanent, and continually frustrated goal of the modern state is to reduce the chaotic, disorderly, constantly changing social reality beneath it to something more closely resembling the administrative grid of its observations.

― James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State

As the early German state sought to maximize timber yields for tax revenue, it began promoting ‘scientific forestry’, initiating “the gradual transformation of forests with a rich diversity of species growing wildly and randomly into orderly stands of the highest-yielding varieties.”

Despite the intention to increase efficiency and profitability, the lack of consideration for the complexity and diversity of natural ecosystems ultimately led to harmful ecological imbalance and decline. By the late 19th and early 20th century, these monocultures revealed their clear vulnerability to disease, leading to a crisis in German forestry that has never truly resolved.

When our communities themselves are made to be more measurable, traditional modes of local responsiveness break down. Without engaged residents capable of sustaining the physical health of a place, economic measures of ‘success’ become instead a self-referential measure of state influence. Like a rejected organ transplant, these artificial structures are eventually resisted and reclaimed, but not without disfiguring our places for decades or more—as has been the case with German forestry.

A Note on States

Of course, states and other government institutions aren’t miserable at everything. They’re useful for managing common legal frameworks, the protection of basic human rights, as well as a check against powerful non-state institutions such as large corporations. In those cases, the state creates a common substrate with which communities can interface more freely. When it comes to local placemaking, though, the modern state's reach strays far beyond clearing space for coordination. Instead, its prescriptive intervention has a habit of suffocating the vitality that trust invites.

Today, it is not just the state’s demand for legibility that is harming rich ecologies. Technological systems for scaling agriculture—like robotic apple harvesters—are making our food systems in their image. Despite the techno-optimist’s sales pitch for robotic farming, long histories of community forestry and communal land management teach us that affectionate cooperation in relationship with natural ecologies produce more healthy, resilient and productive, if less legible, food systems than their institutional or technological counterparts.

We live now in an economy that is not sustainable… because of the increasing abstraction and unconsciousness of our connection to our economic sources in the land, the land-communities, and the land-use economies.

In my region and within my memory, human life has become less creaturely and more engineered, less familiar and more remote from local places, pleasures, and associations. Our knowledge, in short, has become increasingly statistical.

— Wendell Berry, It All Turns on Affection

Affection is Competence

Thriving places simply cannot be planned for by the outside with responsiveness and care. Only people with sufficient proximity and affection enough for the places and people around them can understand the problems they are facing and generate appropriate solutions, even if these aren’t as well-engineered or as justified by data as professional solutions. And so, in the face of a culture of consumption, we work toward capacity for local self-organization. These ideas have been discussed in common by many different people across many different times, including Elinor Ostrom, Jane Jacobs, Wendell Berry, FA Hayek, Karl Polanyi, Christopher Alexander, Ivan Illich, and Gandhi.

In Nepal, locally managed irrigation systems have successfully allocated water between users for a long time. However, the dams – built from stone, mud and trees – have often been primitive and small.

In several places, the Nepalese government, with assistance from foreign donors, has built modern dams of concrete and steel. Despite flawless engineering, many of these projects have ended in failure. The reason is that the presence of durable dams has severed the ties between head-end and tail-end users. Since the dams are durable, there is little need for cooperation among users in maintaining the dams. Therefore, head-end users can extract a disproportionate share of the water without fearing the loss of tail-end maintenance labor. Ultimately, the total crop yield is frequently higher around the primitive dams than around the modern dams.

Relationship and Dialogue

In her Nobel Prize-winning research, Elinor Ostrom analyzed irrigation systems and fisheries all over the world. She found that 72% of farmer-managed systems had high performance (in terms of yield and cost) compared to 42% of agency-run systems, despite having experts and flawless engineering on their side. How is this possible?

The tragedy of the commons is an apparent dilemma often referenced as justification for formalized institutional intervention into resource management. It states that without externally imposed rules, ‘rational’ individual users will overuse resources, depleting long-term and community-wide viability contrary to the common good of all users. This definition of rationality assumes an economy decoupled from relationship.

Ostrom's pioneering research focused on the vital role of coordination in the management of common- pool resources, including forests, irrigation systems, and groundwater. She concluded that groups lacking avenues for communication did indeed abuse their shared resources. She also observed, however, that simply introducing the possibility of face-to-face communication allowed for the kind of greatly increased cooperation that outperformed professionally engineered systems, saying, “policies based on the assumptions that individuals can learn how to devise well-tailored rules and cooperate conditionally when they participate in the design of institutions affecting them are more successful.”

Active participation of users in creating and enforcing rules appears to be essential. Rules that are imposed from the outside or unilaterally dictated by powerful insiders have less legitimacy and are more likely to be violated. Likewise, monitoring and enforcement work better when conducted by insiders than by outsiders. These principles are in stark contrast to the common view that monitoring and sanctioning are the responsibility of the state and should be conducted by public employees.

And so the tragedy of the commons is not some sort of hard scientific inevitability that necessitates institutional oversight from central planners in order to save helplessly ‘rational’ individuals from themselves, but a symptom of an insufficiently relational environment. To move forward, we must reframe what organizational competence looks like. Rather than adherence to institutional best practices, the social and technical capacity for collaborative self-organization is perhaps the most important prerequisite for healthy communities.

To some extent, the answer begins by re-conceiving the built environment itself as social process, not just as product or container.

— Favelas and Social Housing: The Urbanism of Self-Organization

Data Analysis Can’t Replace Community Memory

Capacity for this kind of relational self-organization is built through customs, tools, and technologies embedded in their specific social and ecological contexts. It emerges through dialogue and tradition more often than formal design principles. These generational relationships anchor problem-solving in place and create the kind of local memory required to learn and carry the present into the future.

So, the biggest reason institutions fail to foster resilient communities is not that they lack the computational firepower, but a persistent generational memory. Despite the strength of their quantitative models, the consultants that write the plans for our places are only paid to care long enough to meet the terms of their contract. Over time, incentives fall toward suggesting yet another study instead of following up on previous ideas with no remaining champion—creating loops of wasted effort. Unfortunately these loops often go unnoticed by a disengaged population that has not been invited into the process.

Spontaneity and Informality

It is worth stating explicitly that, while they offer the preconditions for a more relational society, locally derived authority structures can be just as coercive as distant authority.

Subsequent essays will focus on the specific kinds of tools that can foster our capacity for collaboration and build a coherent community memory to counter these tendencies. But, since a healthy society depends on more than simply scorning non-local institutions, we must first better understand what healthy patterns of locally sensitive relationship looks like.

Foundationally, vibrant communities are built on informal, empathetic relationships that leave space for spontaneity. Space granted is an extension of trust capable of producing the kind of breakthrough thinking necessary to solve hard problems and spur on effective social movements.

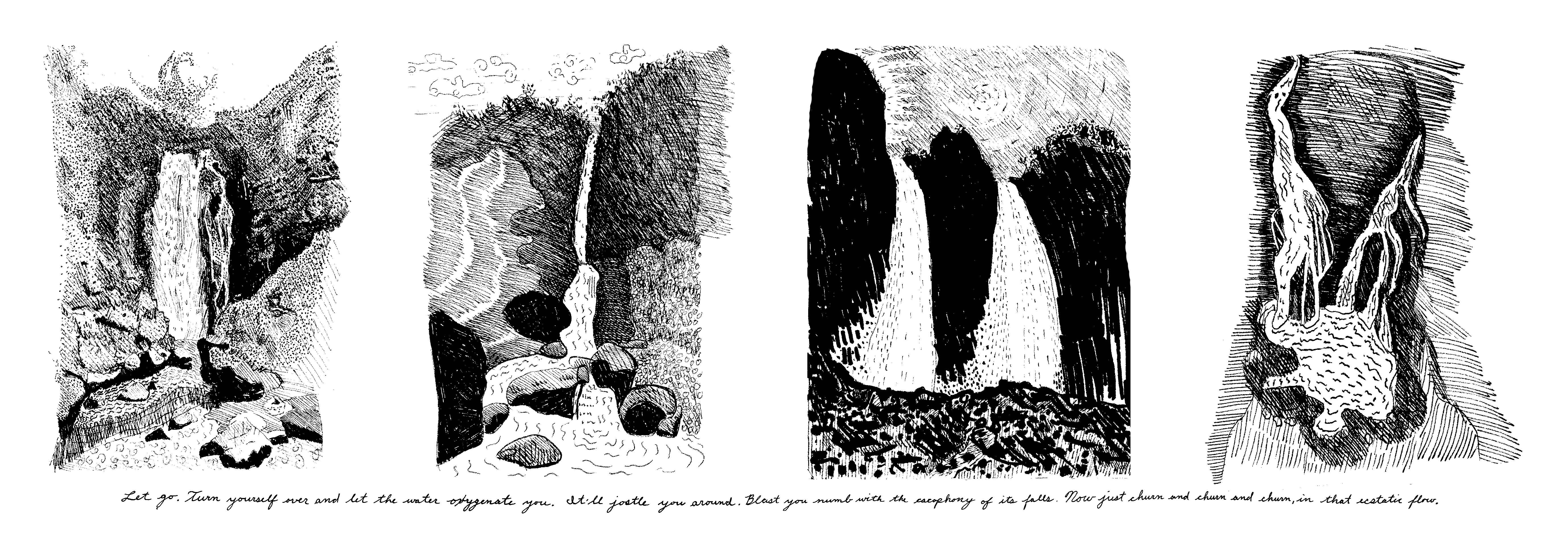

The potency of good art illustrates the significance of such space well, often abstaining from prescribing explicit meaning. The ensuing dialogue between artist and observer invites a vulnerability and openness that cannot be conveyed through formal media with more implied objectivity. When artists give up control over their art by making it public, they enter into an uncertainty that empowers the recipient to make it their own, fueling creativity and hope without fear of rejection or correction.

Relational Places

Even small extensions of trust can go a long way to building healthy relationships between people and a place. The urbanist William H. Whyte famously observed in The Social Life Of Small Urban Spaces that people feel more comfortable in public spaces that allow them to move their chairs. This kind of physical informality builds trust and invites engagement.

The possibility of choice is as important as the exercise of it. This is why, perhaps, people so often move a chair a few inches this way and that before sitting in it, with the chair ending up about where it was in the first place. The moves are functional, however. They are a declaration of autonomy, to oneself, and rather satisfying.

— William H. Whyte, The Social Life Of Small Urban Spaces

Extension of Trust Means Giving Up Power

In community governance, extending trust to individuals and small communities empowers them to change their neighborhoods themselves, reducing reliance on unsustainably distant decision-making processes and providing a richer and more engaging life for their citizens. This empowering trust, however, is in short supply for structures of governance reluctant to give up their influence.

Feigned Extensions of Trust

The reality of complex regulatory and approval processes in our home places means community-building is only accessible to the well-capitalized or well-connected. Even as governments discover that open communication and engagement are important, their half-hearted community meetings are still too often just dressed-up placation that neuter the creative spirit of their constituents. Real engagement can only happen when those with influence start asking what processes can be trusted with community members completely.

Painting and sculpture are now free, inasmuch as anyone may produce any sort of creation and subsequently display it. In architecture, however, this fundamental freedom, which must be regarded as a precondition for any art, does not exist, for a person must first have a diploma in order to build.

— Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Mouldiness Manifesto Against Rationalism In Architecture

Freedom as a Product

While our governments maintain their resource-heavy micromanagement, some of the world’s most successful corporations have succeeded by learning to relinquish control and become platforms instead of product providers.

In Steve Yegge's famous 2011 rant on 'Google vs. Amazon', he shows how centralized decision-making and product release can’t be as dynamic and robust as a platform architecture that enables other teams and individuals to release their own products with minimal oversight. Instead of selling books themselves, Amazon let everyone sell their own books. Eventually, they would expand this posture to their prolific web services as well.

The first big thing Bezos realized is that the infrastructure they'd built for selling and shipping books and sundry could be transformed [into] an excellent repurposable computing platform. The other big realization he had was that he can't … build one product and have it be right for everyone.

Platforms and Products

Platform architectures are now ubiquitous, where in places like Apple's App Store, independent producers offer a wider range of more specialized software than a single company could ever make itself. YouTube and social media platforms similarly host a whole universe of user-generated content.

The difference between these platforms, though, and the agency-delivering organizational structures we should aspire to is that the platform owners can take away access or censor communication whenever they want. Without giving full control to users, platforms can only offer a taste of what more empowering organizational technologies can offer in terms of trustworthiness, interoperability, and permanence.

A Note on Protocols

The progression toward open architectures that empower communities finds its completion in protocols: open standards for organization not controlled by any specific individual or company. These technological building blocks offer the scaffolding for replicable alternatives to central planning and will see much more discussion in the final essays of this series.

Alternatives to Central Planning

How can we build organizational alternatives to dispiriting institutional governance and the false agency of corporate platforms? While some have opted out by eschewing society altogether, we are capable of forming more healthy modes of organization—ones that both honor the complexity of specific places and are benefited by their relationship to a broader society.

Polycentric organizational structures, with multiple centers of semi-autonomous decision-making, are one path forward. In what biologist Michael Levin calls a ‘multi-scale competency architecture’, such aggregated patterns of autonomous local problem-solving are exactly how our bodies self-organize to perform as a whole.

All intelligence is collective intelligence

Advocated for by Elinor Ostrom, these structures grant power to traditional, formalized entities as well as private, voluntary, and community-based non-governmental actors. In this way, higher forms of organization (like state and federal governance) can focus on providing physical and organizational infrastructure that leaves processes and outcomes in the hands of locally originating organizations.

Gandhi spoke of oceanic circles: concentric circles of societal organization where power and action derive from the individual and radiate to the village, region, state, and finally to the nation. This thinking acknowledges the existence of broader contexts of organization without giving them undue power over contexts they cannot properly manage.

In this structure composed of innumerable villages there will be ever-widening, never-ascending circles. Life will not be a pyramid with the apex sustained by the bottom. But it will be an oceanic circle whose centre will be the individual … Therefore, the outermost circumference will not wield power to crush the inner circle, but will give strength to all within and derive its own strength from it.

— Gandhi, Panchayat Raj

Today, community-building practitioners like Microsolidarity are also thinking about concentric governance structures, nested in relationship but non-hierarchical. Their model is structured around a progression from the self-as-a-group → the dyad (2 people) → the crew (about 3-5) → the congregation (about 15-150) → the network of congregations.

Another emerging paradigm, cosmolocalism seeks to strengthen and fortify local manufacturing and resource management by leveraging a globally accessible digital commons. This movement is embodied in makerspaces—community-centered workshops equipped with tools like CNC machines and 3D printers, and full of creators making their often open source designs available globally online. This kind of internet-based collaboration can help local places remain resilient and independent, while sharing valuable information on manufacturing, farming and other necessary skills to their mutual benefit.

A relocalization which does not draw from a global knowledge and design commons and which is relegated to only local knowledge can at best produce ’lifeboat’ relocalization and at worst will not produce basic sufficiency.

When paired with polycentric organizational structures, these kinds of networks can help to proliferate relevant local knowledge across regions. This work is intimate, granting agency at the most local levels, but also affords us the ability to weave these local organizational systems into a collective, supportive whole through mycorrhizal networks of collective and continuous community memory.

Physical Infrastructure for Trust

New organizational alternatives to central planning require some capacity for local mutual trust exactly at the time when it has gone missing. In his 1925 book The Collective Memory, Maurice Halbwachs established the deep influence that physical places have on the ability of communities to maintain and transmit their collective identities and histories.

Most groups engrave their form in some way upon the soil and retrieve their collective remembrances within the spatial framework.

— Maurice Halbwachs, The Collective Memory

Eric Klinenberg’s 2018 Palaces for the People continues in this lineage, exploring how social infrastructure—physical infrastructure that embeds social relationship into daily life— helps make people happier, more trusting of their neighbors, and even safer in crisis.

During the 1995 Chicago heat wave that killed 739 people, certain neighborhoods produced fewer deaths, even when accounting for other social factors like race and income. Klinenberg found the reason was that these neighborhoods had better social infrastructure—like shaded sidewalks, active street-level vendors, and libraries that facilitated social relationships. Neighbors in these places were much more likely to check in on each other during the heatwave or notice that a certain neighbor was missing from their daily routine.

As an alternative to the kind of agency-eroding surveillance in the name of safety currently being marketed to cities, communities have the opportunity to raise up physical infrastructure to foster safety nets of neighborly affection that both make us happier and save lives.

Can Technology Help?

While well-cared-for places serve as the cornerstone of a sustainable society, we cannot love them well without suitable tools of coordination. Despite its recent contributions to our collective forgetting of generational stewardship, technology should not be viewed as the enemy of local resilience. The distinction must be made between technologies that empower local agency and those which create dependency on outside resources.

Culture and individual memory are constantly produced through, and mediated by, the technologies of memory.

— Marita Sturken, The Memory Remains

Wonderfully, the world of open-source software development has shown us that it is possible to challenge institutionalized norms and build parallel systems of organization with real legitimacy, especially with the internet as a substrate for coordination. In subsequent parts of this series, we’ll discuss explicitly how new protocols for coordination can help move our physical communities toward a society with more agency.

A memento for this essay can be found

here.