1

Relationship

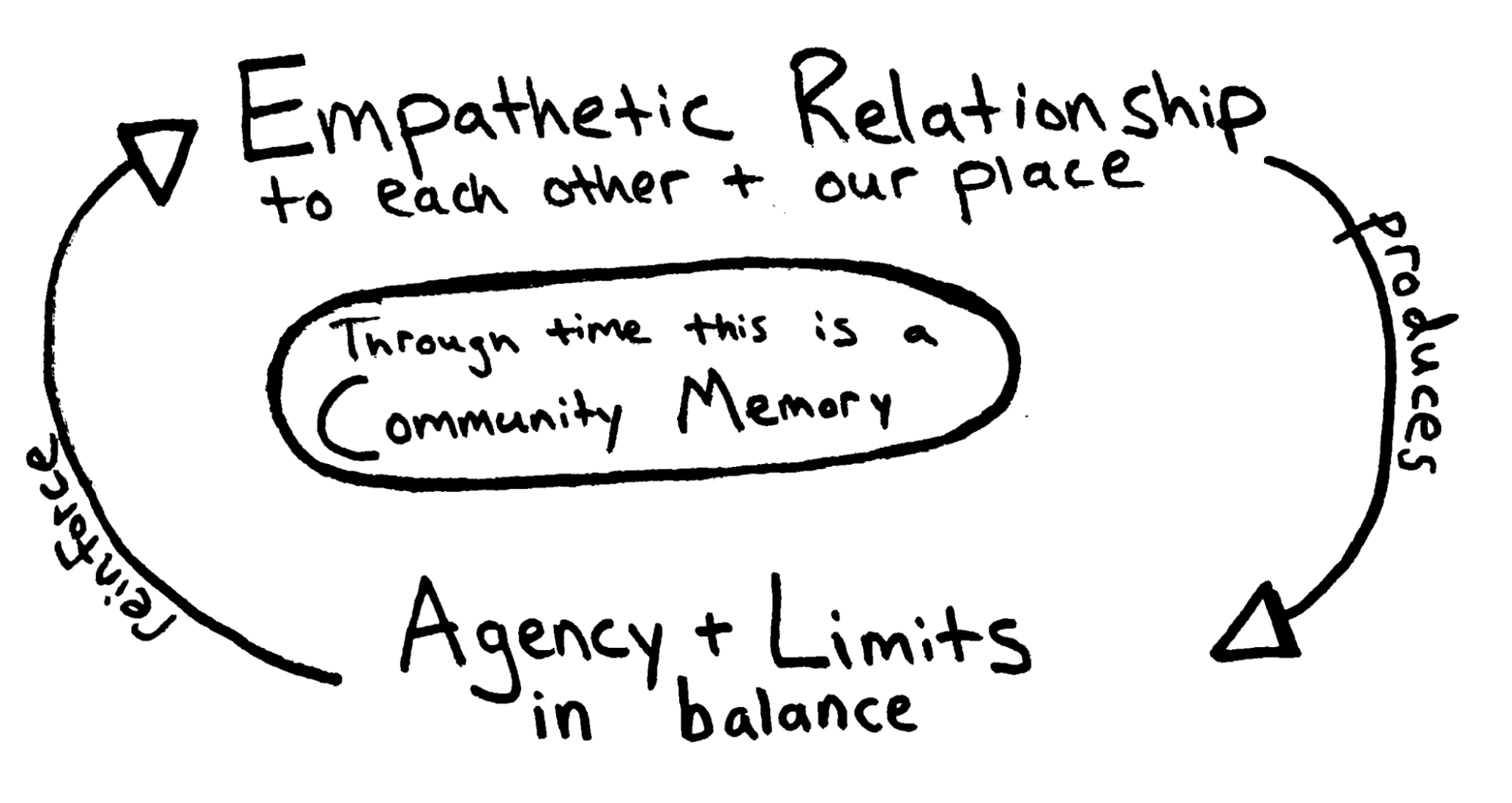

Balancing Agency and Limits Toward Empathetic Placemaking

Despite the proliferation of impersonal organizational structures and abstract global economies, only the mutual extension of trust—grounded in affection for our home places—can foster traditions of placemaking strong enough to steward our communities sustainably through generations.

Community Memory

Why did bureaucratic efforts to stimulate economic growth instead wreak havoc on one of the world's largest lakes? And how is it that ‘uneducated’ peasants have collectively managed thriving irrigation systems for centuries in New Mexico, Indonesia, Spain, and India?

The answer lies in the power of community memory—a shared and living capacity for action grounded in relationship to our neighbors and our place, from which emanates a joyful balance of agency and limits.

This first of six essays will explore why this equilibrium of empowering agency and grounding limits is so important to sustaining healthy places across generations. Subsequent sections will examine how new technological approaches to collective coordination—from participatory budgeting to local currencies—can reduce our reliance on disempowering institutions and mature a community memory toward more resilient home places. Foundational to this resilience is agency.

Agency

Agency is the capacity to shape the world around (and within) us through action. The fields of psychology and mental health have well established this power for self-determination as a vital factor for a healthy life. It allows us to engage more deeply in ways that improve memory, happiness, and resilience in the face of challenges. Without agency, we disengage and are less successful in building healthy and sustainable habits.

While experienced by the individual, a rich and enduring faculty for self-determination can only be achieved when we produce agency for each other in the mutual extension of trust and empathy. This kind of relationally imbued self-efficacy has been shown to correlate with recovery from mental illness. Conversely, a key marker of an unhealthy relationship is one where a partner’s right to self-determination is reduced—and yet we consider a lack of agency in making our communities to be normal and even necessary.

Limits

Empathetic relationship is vital not only for agency-building, but also the formation of mutual and responsive limits that ensure that the exercise of agency does not compromise the long-term health of our places. As technology broadens our propensity for consumption, this relationship to limits becomes increasingly important.

It is not that natural limits have been transcended, but that technology allows us to more easily externalize the effects of our consumption beyond our home place. Agbogbloshie in Ghana, now a global dumping ground, is one of many places that has seen its future shaped by the waste of outsiders.

When we find ourselves in the habit of depending on ‘somewhere else’, eventually we may too find our homes implicated in such an abstract system of economic relationship. Fostering agency in a globally connected, technologically enabled society, then, depends on our collective capability to conjure a sufficient source of discipline. But where might it come from?

Limits Derived in Institutions

In the absence (or doubt) of local capacity for disciplined stewardship, institutions attempt control to produce moderation but achieve neither. Instead, leaving us with a self-reinforcing arms race of scale between abstract economies and any broad regulatory structure erected to manage them.

As their scope of influence broadens, institutions reshape the places they attempt to manage in their own image—reducing them to statistical averages and summarizations derived in the postulations of people with more credentials than context or affection. Despite their obsession with absorbing data, modern economies and their metastasizing institutions simply cannot produce enough understanding to reason about limits with meaningful sensitivity.

Limits Derived in Empathetic Relationships

Organizational structures anchored in affectionate dialogue provide a more proprioceptive framework for establishing sustainable limits than prosthetic institutional decision-making processes. Only by such an embodied memory of local placemaking traditions can we cultivate empathetic understanding and respect for our constraints and attune ourselves to the specific ecology of our place.

Enduring structures of household and family life or the life of a community or the life of a country, cannot be formed except within limits. We must not outdistance local knowledge and affection.

— Wendell Berry, The Art of Loading Brush

The Persistence of Place

Places embody our cumulative, collective memory. They are uniquely persistent in their effect on culture from generation to generation, more enduring even than the organizational structures that manage them. The consequences of poor caretaking are painfully clear in almost every American city today as the same institutions that gutted downtowns in service of highways now try to amend those mistakes 80 years later.

Decisions made about our places today will impact many generations to come, and yet most Americans have no role to play in building and maintaining their own neighborhoods.

Experts and Consumers

The path of least resistance in American culture today is to be a consumer of place as product, just as we are consumers of lawn maintenance, home cleaning, and cooking services. Our politics invite us to be spectators more often than participants, and even the parenting of our children is increasingly outsourced to experts. This pattern is reinforced in our increasingly specialized work lives, where power accrues to C-suite decision-makers removed from the work. And so, in the making of our places, we too are often left as passive speculators on the abilities of experts and a footnote in a municipal report on 'community engagement'.

Generations of planners creating for ‘customers’ has dampened our sense of self-efficacy in placemaking. When the value of our places is determined by the application of expert knowledge rather than by local interpersonal cooperation in step with local ecology, less care and attention is applied—especially as time distances planner from planned.

[His] aim was the creation of self-sufficient small towns, really very nice towns if you were docile and had no plans of your own and did not mind spending your life with others with no plans of their own. As in all Utopias, the right to have plans of any significance belonged only to the planner in charge.

Today the power to change a neighborhood is primarily reserved for ‘visionaries’ with enough political power, expertise or money to navigate institutional processes. While such a dynamic expands the capacity for large-scale change, it hinders the ability of small actors to respond incrementally to the problems they experience in their own homes and neighborhoods. This style of central planning not only ends up making inaccurate generalizations about the specific places it changes, but it also lulls those who it plans for into a sleep-like dependence on external authority.

In further institutionalizing the great power of the majority, we are making the individual come to distrust himself. We are giving him a rationalization for the unconscious urging to find an authority that would resolve the burdens of free choice. We are tempting him to reinterpret the group pressures as a release, authority as freedom.

― William H. Whyte, The Organization Man

Disengagement

Over time, not being trusted with community-building has made us apathetic. Engagement in local governance is at an all-time low and it is now common for people to live without any connection to their neighbors, neighborhoods, or local history. Our habit of consuming has rendered us increasingly willing to depend on outsourced management of our places, whose expertise we hope can absolve us of any obligation for collaborative stewardship and affection.

This craving for absolution is no surprise given the well-studied paradox of choice, which argues that the glut of possible paths available to us in modern society is a major source of anxiety and fatigue. When modes of making a living no longer require local knowledge, schools are willing to teach anything as long as you pay, and all work can be done remotely, we come under the weight of choosing our life from a buffet of all possible happinesses—and find none.

Generational memory, tradition, and a connection to our home places are exactly the things that have traditionally produced lighter individual burdens of choice in the past—but ironically, they themselves are now outsourced to the institutional structures whose depersonalizing abstractions make them impotent.

The longer our apathetic dependence on distant and opaque systems of organization goes on, the more out of tune we become with traditions of placemaking that have grown alongside the specific ecology of our place. Eventually, our collective memory loss can render these traditions unsalvageable–shifting our connection with extractive economies from a convenient way to raise ‘standards of living’ to a dangerous dependence on fragile gentrifying systems beyond local control.

This pattern is evident in many rural American communities, where nonlocal retailers like Walmart and Dollar General initially disrupted local economies, replacing groups of locally owned businesses with a single store. Over time, communities have grown reliant on these corporations for jobs and access to food, only to again see disruption when the retailers choose to close or move.

Catalysts of Change in a Society Managed at Scale

For most communities defined by numbing, impersonal economies managed by large institutions, the fog of our listlessness only lifts when something breaks.

Such shock events provide space to reevaluate and engage with the deeper structure of society. Because incumbent institutions and economic relationships adapt slowly to these new realities, individuals and small communities find themselves more capable and ready to implement solutions independently, without oversight or permission. These interventions ultimately prove to be a catalyst of longer-term change—as was apparent in the wake of COVID-19, which invited changes not just in remote work, but also healthcare, public space, transportation, outdoor dining, supply chains, and more.

This phenomenon can also often be observed after a pedestrian death, often the only time when communities sufficiently mobilize to prioritize safer transportation infrastructure. In these instances, citizens take matters into their own hands or local demands for change become so loud that even a state transportation agency can be moved to action. The rise of tactical urbanism and other DIY urbanism is further evidence of this impulse.

Despite positive outcomes from wake-up call events, we shouldn't depend on pandemics and pedestrian deaths to drive positive change in society. If we embrace new (and old) empowering models for collaborative placemaking, we can instead develop habits of resilience and problem-solving that don’t require catastrophe to initiate change—a community memory that produces a persistent lucidity.

Where Do We Start?

The study of long-sustained water and forest management systems teaches us that building resilient places protected from catastrophe requires iterative and ongoing management in tune with local ecology. Just as prescribed burns are often carried out on foot at a careful pace to prevent larger disasters, we must cultivate smaller-scale organizational and economic structures that empower local people to maintain their specific place with care and affection. Only then can we begin the work of weaving a dynamic, resilient society of our home places.

A memento for this essay can be found

here.